The quest for explanations

Previously, I showed how several monodisciplinary causal maps can be combined and integrated to form an interdisciplinary causal map. This meant skipping over a key question: how do you turn knowledge from literature or experiments into (hypothesized) causal mechanisms?

In this post, I will try to offer a structured approach to populating a causal map. It should be said, however, that causal mapping is an exercise careful yet creative reasoning. You will have to identify relevant components that can help explain your topic of choice and see how they interrelate, mostly by evaluating the options that you have and avoiding blind spots.

The following procedure is based on the idea that you are less likely to have blind spots if you consider all types of explanation that are out there. I've previously laid out four main types of explanation that are used in scientific practice: casual explanations, goal explanations, constitutive explanations and contextual explanations.

If you systematically go over the various types of explanation for the relations in your causal map, you are likely to gain a better description of your explanandum. I realize there's a scaling problem here: for large causal maps it is unlikely that you can deeply explore four different explanation types. Feel free to focus just on a corner of interest of your causal map (and consider pruning corners you do not find interesting at some point in your process).

Once you have found explanations (either using your own background knowledge or through active literature research), you will need to turn them into causal explanations so that they can be meaningfully added to your map. Remember that the causal map is supposed to give you an overview – overcomplicating it defeats its purpose.

Causal explanations

To start off, think of causal explanations for a given component of your causal map. If you have no components, just start with the explanandum. Which processes or components are brought about by the component you're considering? Which steps were required to end up with the component? Causal explanations are the type of explanations that are visualized in a causal map: once you’ve thought of a chain of events connected to a given component, you can draw it out as a series of new components.

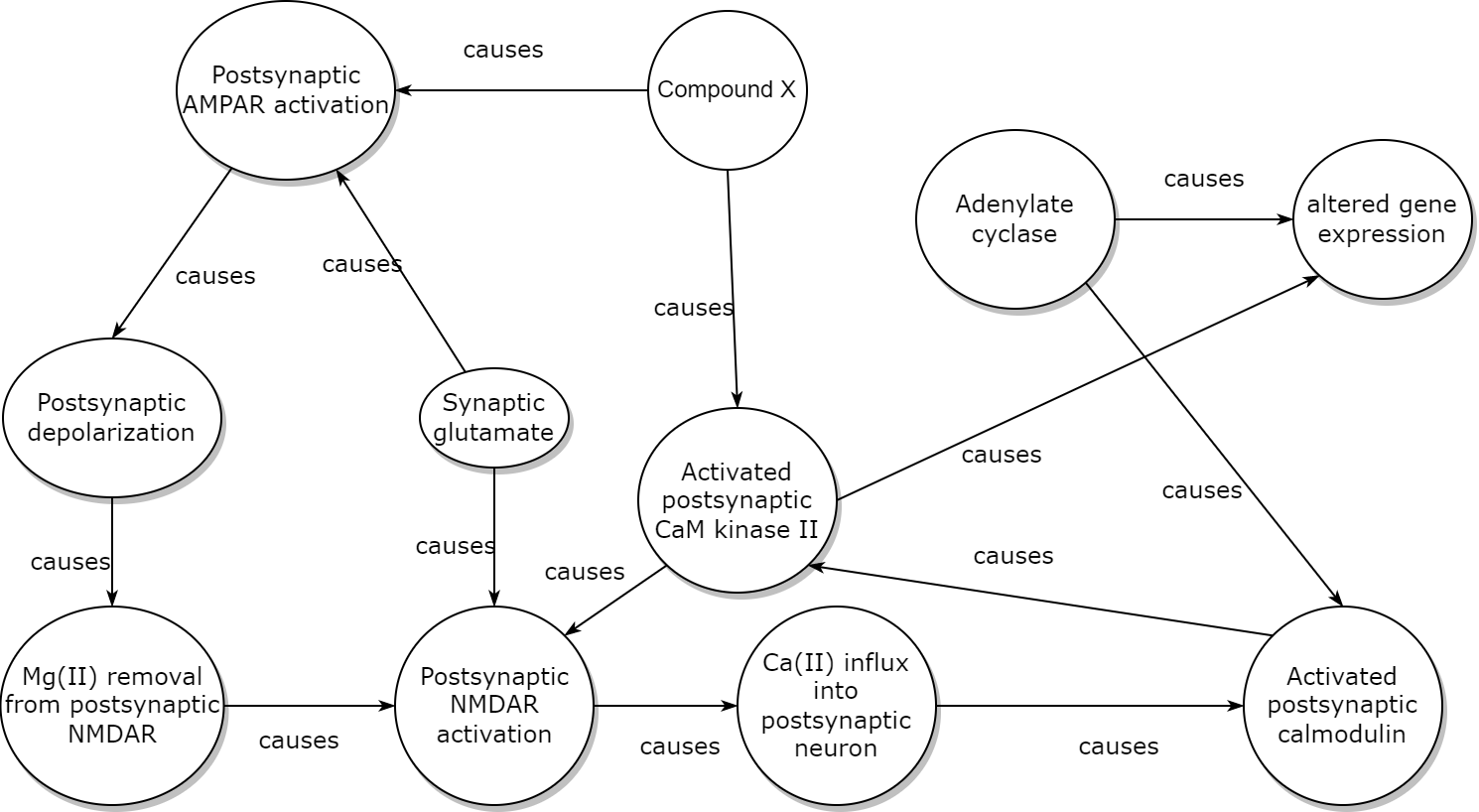

Consider again the neurobiologist's causal map (and don't worry about its technical details). Starting from ‘Compound X’ and the goal of explaining long-term potentiation, she claimed that Compound X acts via activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and post-synaptic AMPA receptors, which in turn lead to further cascades of molecular biological events. Her map is a big causal explanation for the effects of Compound X.

Some care should be taken when visualizing causal relations. The goal of a causal map is to keep a clear overview, so it’s important to make economical decisions about what to include, and how to do so. For example, the above neurobiological causal map leaves out that kinases do their job by phosphorylating other molecules, and instead just states that the kinase “causes activated calmodulin”. Similarly, some nodes refer to specific elements in the causal chain, while others refer to processes — this was done to keep things neat in an already complex web of causal relations.

Constitutive explanations

Once you have a list of causal explanations, consider if there are any constitutive explanations that are related to your most interesting components. What are the components made of? How can their properties be explained by underlying structures and processes? Do one or more components form a new one at another level of description?

Turning constitutive explanations into causal explanations can be done in two ways. The easiest way is to just label the arrows in your causal map as 'constitutes'. This makes sense if you do not want to zoom into the constitutive relation too much. A more complicated way is to define 'levels' in your map and to draw constitutive relations at different levels. This gives a multi-level explanation, which can be useful for interdisciplinary work. We will return to multi-level explanations at a later stage.

Goal explanations

Another way to think about possible causal relations is to think about goal explanations. What is a component good for? What purpose does it serve? This is not a meaningful question in each discipline, but in some (such as in social sciences or humanities) it can be very helpful to think about intentions and purposes.

Now it might be that goal explanations do not lead to especially strong causal relations. While a power plant can reasonably be claimed to ’cause’ power supply in practice, it might be debatable whether a pottery class really boosts creativity, even it was designed to do so. Yet this does not mean the relation should not be part of your causal map. It just means that you need to critically look at the evidence for the connection.

There are circumstances in which it is not straightforward to map goal explanations onto causal explanations. For example, a biologist might draw a causal map in which the components and processes of the heart cause blood circulation in a given organism. That is, after all, the purpose of the heart. Yet in an evolutionary sense, the blood circulation (or rather, the differential reproduction caused by improved blood circulation) causes the components and processes of the heart! A causal map showing both levels of description can easily become unreadable.

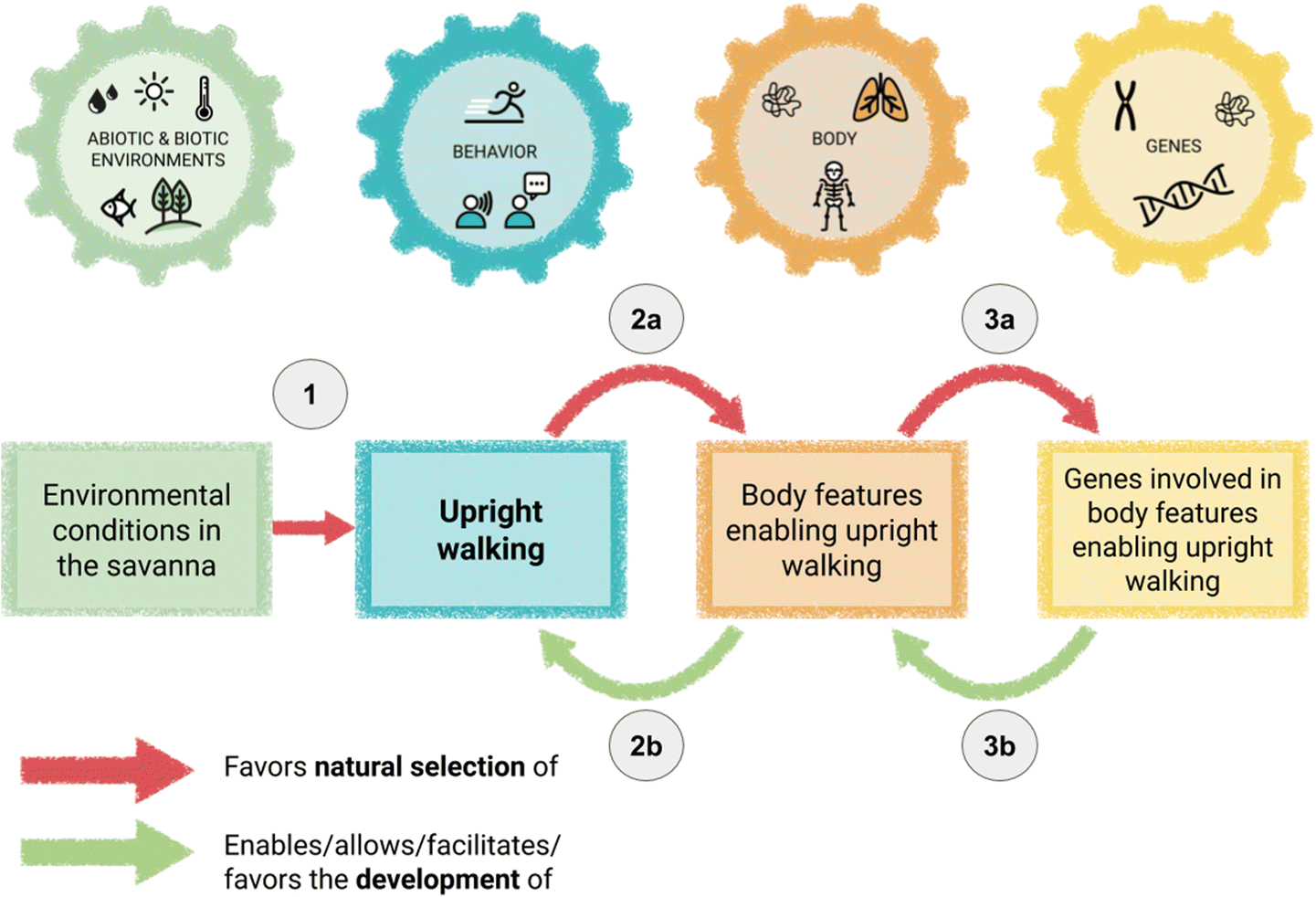

One way to solve this is to carefully label the causal arrows, differentiating between their levels of description. Take the following example, taken from a description of causal mapping in evolutionary biology education (Hanisch & Eirdosh, 2020). In this example, the authors distinguish between evolutionary and developmental processes as different forms of causality, while also clearly separating the genetic, organismic, behavioural and environmental levels.

Contextual explanations

A final type of explanation that can help identify relevant causal processes is the contextual explanation. The aforementioned power plant causes power supply for a city, assuming the context offers a functional electrical grid. Cognitive control can limit pre-potent responding, except in the context of tiredness or significant alcohol consumption.

In some cases, contextual explanations can inspire you to add a new component to a given causal chain, but generally it is better to have contextual factors modulate causal connections. You can have a component 'functional electrical grid' point to the relation between 'power plant' and 'power supply'. Only add contextual factors if they are relevant to your research interest!

If you think about relevant contextual explanations, you will often be identifying factors that you’ve been assuming to be fixed — and these factors may be described by wholly different disciplines than the ones you were initially considering.

Generating a causal map

By thinking of these four explanation types — causal explanations, constitutive explanations, goal explanations and contextual explanations — it is possible to define causal relations that can be visualized in a causal map. Of course, a causal map should not become overly complicated: its aim is to provide a clear overview of those causal relations that are relevant to a research interest. However, systematically addressing different explanation types avoids blind spots and may help to anticipate factors from disciplines outside of your own.

Once you have gone through this process, you should have a rather detailed causal map. This is a good moment to think about the actual research question you want to ask. Once you have defined a research question, it will be time to prune the causal map. Afterwards, the time has come to critically evaluate the components and causal relations you have left.

References

Hanisch, S., & Eirdosh, D. (2020). Causal mapping as a teaching tool for reflecting on causation in human evolution. Science & Education, 1-30.

Member discussion