Reasoning about fake news

Does the spread of fake news suggest that people cannot distinguish truth from fact if it doesn’t fit with the interests of their in-group to do so? A recent review suggests otherwise, instead claiming that discerning true news from fake news is a matter of reasoning. This reasoning is not so much affected by irrational effects of group identity, but rather by arguably rational effects of prior beliefs and knowledge.

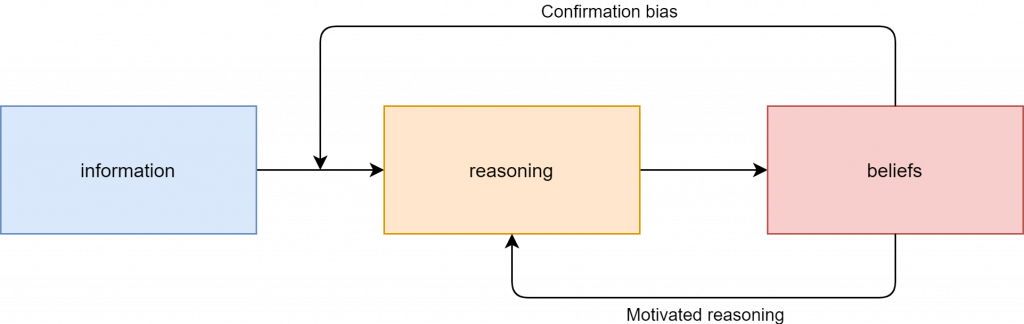

When we seek out to learn about the world, there are two important processes that can hinder our reasoning. One of these is the confirmation bias: the tendency to seek out and select information that meets beliefs we already have. The other is motivated reasoning, which bring us to process information in such a way that it is compatible with the beliefs we already have.

The use of these terms has been loose, both within and outside of psychological science. While the original formulation of confirmation bias was very narrow and limited to the way humans reason about rules (Wason, 1968), it soon encompassed wholly different issues, such as the way we seek out new information, the ease with which we can think of arguments that support our claims or refute counter-claims, or the lopsided way in which we handle novel ideas — to the point of it overlapping with the concept of motivated reasoning. This has helped to drive home the point that our cognitive processes are permeated with a ‘myside bias’ at a wide range of levels (Mercier, 2017), but came at the cost of conflating distinct cognitive processes, each with their own specific features.

Indeed, confirmation bias often gets the blame in discussions about fake news. The narrative then is that the confirmation bias steers us towards false beliefs and renders our biased cognitive systems sensitive to hijackers. Yet as Figure 1 illustrates, this is only true to the extent that such hijacking can occur by filtering incoming information. After that, the reasoning process is skewed not by confirmation bias, but by motivated reasoning — a different beast altogether.

Motivated reasoning is partially driven by social cognitive processes, such as wanting to have the same beliefs as your in-group. This aspect has received a lot of attention in political psychology, as it may explain the observation that political partisanship can influence the way people evaluate new information. Yet another part of motivated reasoning is simply checking whether new conclusions fit with your pre-existing beliefs or knowledge — something we would call plausibility checking if we deem those prior beliefs to be reasonable, and belief bias if we don’t.

In a recently published review in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Gordon Pennycook and David Rand discuss the psychological literature on fake news (Pennycook & Rand, 2021). They distinguish between belief bias and politically motivated reasoning, identifying the former as reasoning on the basis of prior beliefs and the latter as reasoning in accordance with political partisanship. The evidence, they argue, is not in line with people accepting fake news if it just so happens to suit their political preference: telling apart true and fake news depends first and foremost on how good participants are at reasoning.

Additionally, they claim that belief in fake news is not so much driven by politically motivated reasoning as it is by belief bias (or plausibility checking) — the things that people already believe or know and against which they measure the plausibility of new information. In daily parlance, political identity and beliefs are always intertwined, but this research suggests that it is useful to separate political group identity from the contents of the associated belief system, and to consider both as separate modulators of reasoning processes.

Pennycook & Rand also claim that prior knowledge inoculates against believing fake news, which contrasts with findings that political knowledge can increase motivated reasoning among experts (Taber & Lodge, 2006) and conspiracy theorists (Miller, Saunders & Farhart, 2016). Making reasoners more knowledgeable in relevant domains, as well as improving their reasoning and reflection skills, would then go a long way to battle belief in misinformation.

That is, at least, if social or political identities do not stabilize specific inaccurate beliefs, despite being distinct from them. In an earlier post on conspiracist ideation, I suggested that such stabilization effects might in the end obstruct attempts to promote reasoning and critical thinking. As belief bias appears strengthened by expertise (Tappin, Pennycook & Rand, 2020), knowledge training against fake news requires not just adding accurate beliefs, but also removing inaccurate ones, which may come at a social cost.

References

Mercier, H. (2017). Confirmation bias—Myside bias. In R. F. Pohl (Ed.), Cognitive illusions: Intriguing phenomena in thinking, judgment and memory (p. 99–114). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824-844.

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in cognitive sciences.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American journal of political science, 50(3), 755-769.

Tappin, B. M., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Rethinking the link between cognitive sophistication and politically motivated reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Wason, P. C. (1968). Reasoning about a rule. Quarterly journal of experimental psychology, 20(3), 273-281.

Member discussion